In March 2020, the entire world was thrown into turmoil thanks to the raging COVID-19 pandemic. Much of the globe went into lockdown fearing the deadly virus. People purchased masks, hoarded toilet paper, and canned food. Hand sanitizer flew off store shelves. Fast-forward nearly two years later, few could have anticipated the drastic increase in addictive behaviors experienced during lockdown. Psychologists have tried to understand the reasons behind compulsive addictive behaviors for years by conducting clinical studies and using animal models.

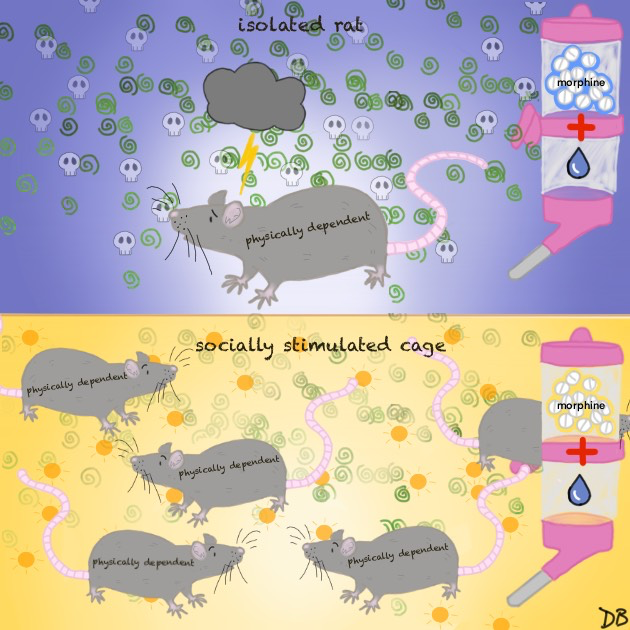

In the late 1970s, Dr. Bruce Alexander, a Canadian psychologist, conducted a series of experiments called ‘Rat Park.’ He separated rats into two experimental conditions. One group was exposed to a socially stimulating environment with lots of other rats. In the other group, the rats faced isolation. Each group was supplied with self-dispensing bottles that provided plain water and morphine-laced water to measure the effect of their environment on the addiction rates. The experiment showed that while the rats in both cages became physically dependent to morphine, those in the socially-stimulating condition resisted the morphine water. These animals also consumed a lot less intermittently whereas the isolated rats consumed more of the morphine-laced water and overdosed. These experiments introduced the idea of environmental factors playing a huge role in addiction.

Humans may be much more complex than rodents, but this experiment combined with data on drug and alcohol use clearly indicates that it is a mistake to underestimate the significance of environmental factors. According to the authors of “The Genetic and Environmental Bases of Addiction,”an article on Neuroanthropology.net, the use of drugs and alcohol is a learned behavior, which is illustrated by the cultural emphasis society has placed on learning ‘how’ to drink.

So, what is the relationship between two completely disparate things – long-term social isolation during the COVID-19 lockdown and addiction?

According to an article published in The Journal of Neuroscience, isolated rodents have more aggressive characteristics. Not only are they more likely to become dependent on the drug they are exposed to, but they also show increased anxiety and aggression, as well as deficits in spatial learning. Similarly, during quarantine, many people have been more isolated for months, unable to leave their homes or socialize normally. Unfortunately, in such situations, turning to the comfort and euphoric high of drugs or alcohol can help quell a person’s loneliness and intrusive thoughts, which is exactly what happened.

In August 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported 13% of Americans either started or increased substance abuse in response to isolation anxiety caused by the pandemic. Addiction behavior is stressful for individuals and the health care system. How can rodent models of addiction help us understand human addiction behaviors?

A Tufts University study on opioid addiction compared reward systems between humans and rodents. These systems are designed to make an individual repeat a behavior because they find it pleasurable. Due to this similarity, rats can serve as great models for the study of human addiction and human substance-use disorders. Both humans and rats experience relapse in a similar way. When you take the drug away from an individual and then place them in an environment that reminds them of the drug, both species will start searching for it.

Dr. Marco Venniro, an expert on addiction studies from the University of Maryland agrees, “Behavioral similarities between humans and rodents exist. Rodents crave for social interactions, just like humans. Rats love to socialize with other rats and are very similar to humans in the usage of drugs. Rats and humans alike, will take drugs despite adverse consequences. If you mildly shock them while [the rats] are seeking drugs, they continue to take the drugs and when you provide social interaction they respond positively, similar to humans.”

Dr. Venniro also shared, “different patterns of addiction and infusion were observed in rats when given opioids like fentanyl compared to cocaine which is a psychostimulant.”

According to the CDC, Fentanyl has been implicated in approximately 60% of drug-related deaths during the pandemic. While creating rodent models for addiction can show how environmental factors play a huge role, they can also help us learn how social rewards can be used to treat and prevent the problem in humans. However, there are many other factors that influence this complex concept.

Environment isn’t the only component of addiction. Scientists have known for a long time that genetics are influenced by the environment. The studies on the effect of genetics on addiction behaviors have revealed a strong connection between genes and addictive behaviors. During a doctor’s appointment, the forms we are typically required to fill out ask about a person’s family history with alcohol or smoking. This information is crucial to the care provider because genes influence the numbers and types of receptors in peoples’ brains, as well as how their body metabolizes drugs and responds to different medications.

More than 30 years ago, Dr. Pier Vincenzo Piazza and a team of researchers from the University of Bordeaux introduced rats as models to characterize genetic differences in individuals with drug abuse and addiction tendencies. They discovered, similar to humans, only some rats readily self-administer addictive drugs. They found this propensity to take drugs could be readily predicted by a behavioral trait which they referred to as “sensation-seeking.” The high-responder (HR) rats, or those that exhibited increased locomotor activity when placed in a new environment, were more likely to self-administer drugs of abuse like amphetamine, cocaine, morphine and ethanol relative to low-responder rats (LR), or those with low levels of activity in a novel environment.

Another group of researchers led by Dr. Shelly Flagel from the University of Michigan and the University of Alabama focused on the behind-the-scenes activities of this differential vulnerability to addiction. The team’s work focused on the brain’s pleasure center. They examined the level of gene activity and how it is affected by gene regulation in early development. They studied two gene candidates previously implicated in HR/LR differences. The team’s findings suggested the low gene activity of one of the genes in the pleasure center of the brain may render individuals more susceptible to cocaine addiction, while the low levels of the other gene may serve as a protective factor. These studies can potentially help identify genetic causes of addiction in families and help patients with targeted treatments.

What does the future hold?

Despite decades of research, addiction continues to be a deep-rooted disease in society. Dr. Venniro shared his thoughts, “Addiction research needs a reset. We have been stuck for 40 years. If we have to fail, we should fail rapidly so we can move on to new methods and models and progress rapidly. It is the moment in science to come together and improve interventions. I hope that in 5 to 10 years I can collaborate with clinicians in performing translational research to make great strides in addiction research.”

- Psychologists have long tried to understand the reasons behind compulsive addictive behaviors through clinical studies and research using animal models.

- Several behavioral similarities between humans and rodents demonstrate these animals can provide valuable data when it comes to addiction research.

- While progress has been admittedly slow, it is hoped research in both animals and humans can significantly advance the availability of interventions for those fighting addiction.

Sources

Czeisler, M. È. (2020, August 13). Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the Covid-19 Pandemic – United STATES, JUNE 24–30, 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6932a1.htm?s_cid=mm6932a1_w.

Singer, Bryan. “Are Cocaine-Seeking ‘Habits’ Necessary for the Development of Addiction-Like Behavior in Rats?” Journal of Neuroscience, 3 Jan. 2018, www.jneurosci.org/content/38/1/60.

Dlende, A. (2008, May 6). The Genetic and Environmental Bases of Addiction. Neuroanthropology. https://neuroanthropology.net/2008/05/06/the-genetic-and-environmental-bases-of-addiction/

Flagel, S. B. (2016, May 17). Genetic background and epigenetic modifications in the core of the nucleus accumbens predict addiction-like behavior in a rat model. PNAS. https://www.pnas.org/content/113/20/E2861

Kuhn, B. N. (2019, November 29). Understanding Addiction Using Animal Models. Frontiers. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnbeh.2019.00262/full

MacBride, K. (2017, September 5). This 38-year-old study is still spreading bad ideas about addiction. The Outline. https://theoutline.com/post/2205/this-38-year-old-study-is-still-spreading-bad-ideas-about-addiction

Nelson, A. (2020, March 13). What Opioid Use in Rats Can Tell Us About Addiction in Humans. Tufts Now. https://now.tufts.edu/articles/what-opioid-use-rats-can-tell-us-about-addiction-humans

Perlman, W. R. (2021, February 18). Rats Prefer Social Interaction to Heroin or Methamphetamine. National Institute on Drug Abuse. https://www.drugabuse.gov/news-events/nida-notes/2019/08/rats-prefer-social-interaction-to-heroin-or-methamphetamine

Piazza, P. V. (1991, March 15). Corticosterone levels determine individual vulnerability to amphetamine self-administration. PNAS. https://www.pnas.org/content/88/6/2088

Sederer, L. I., MD. (2020, November 16). What Does “Rat Park” Teach Us About Addiction? Psychiatric Times. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/what-does-rat-park-teach-us-about-addiction

Society for Neuroscience. (2017, November 20). Realistic rodent model of drug addiction: Ingenuity, not habit, sustains addiction in rats. ScienceDaily. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/11/171120141511.htm

Spanagel, R. (2017, September 1). Animal models of addiction. PubMed Central (PMC). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5741108/#:%7E:text=Mice%20and%20rats%2+0can%20also,high%20degree%20of%20face%20validity

Editorial Team

- Chief Editor: Karishma Goswami

- Team Editor: Adwaith Hariharan

- Creative Team Managers: Daniela Benoit, Bebe Lemanowicz

- Social Media Team Manager: Spencer Lyudovyk

- Image Credits: Daniela Benoit, Bebe Lemanowicz

Mentor

- Amy Puffenberger holds a Bachelor of Science in Film and Video Production (2005) from Grand Valley State University and a Master of Arts Management (2010) from Carnegie Mellon University. While completing her master’s degree, Amy worked with both Pittsburgh Filmmakers and the Arts Education Collaborative, and later served as the Manager of Educational Outreach at WQED Multimedia, the PBS-affiliate in Pittsburgh, PA, and the nation’s first community-supported public broadcaster.

Content Expert

Dr. Marco Venniro is an Assistant professor at the University of Maryland, School of Medicine, Baltimore. His research is focused on understanding how alternative non drug rewards like social rewards can be used to control and treat drug addiction. His lab is developing translationally relevant operant models of addiction and social behavior in rodents to understand the complex problem of drug addiction and other neuropsychiatric disorders in humans.

Publications: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=venniro%20m

Lab: https://www.vennirolab.org

Twitter: https://twitter.com/MarcoVenniro