When was the last time you had a scratch, cut, burn or bug bite? It’s hard to remember such trivial things, isn’t it? On the other hand, picture this: a hand like a zombie’s, with some parts swollen and rotten. That image is a lot harder to forget, and perhaps you should feel lucky that the scratch, cut, burn or bite is so forgettable, because in some circumstances, they could turn your skin into something that resembles a zombie!

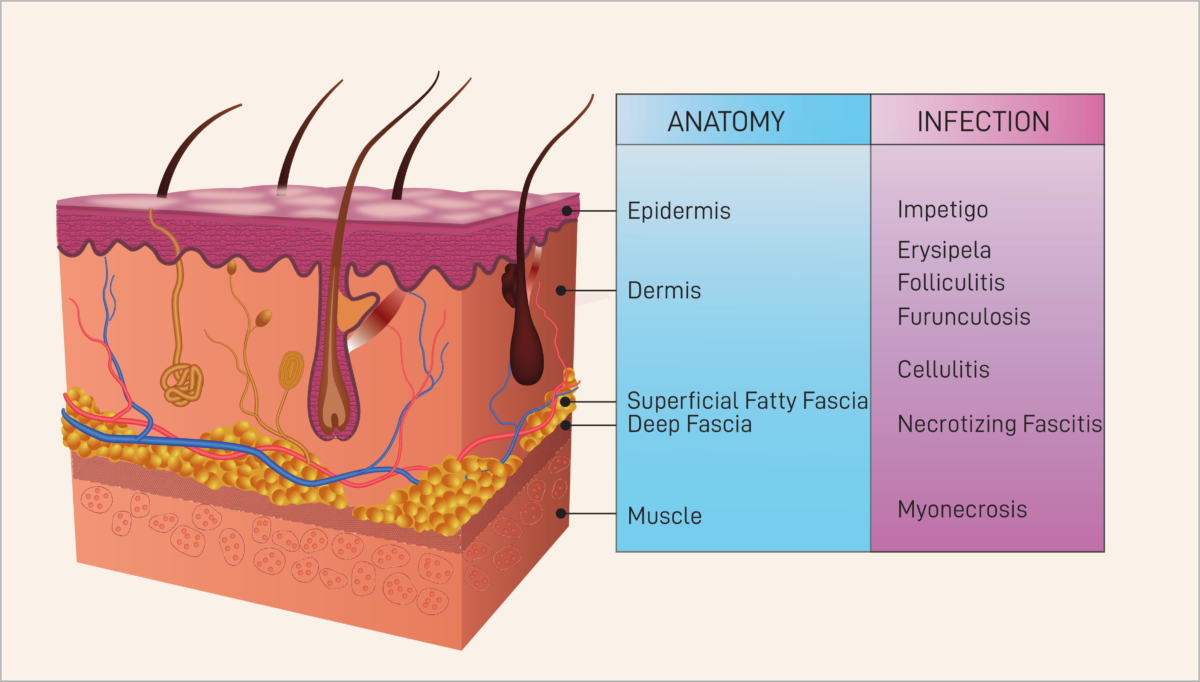

Such conditions can arise from necrotizing fasciitis (NF), an ailment more commonly known as flesh-eating disease. A form of bacterial infection, the disease suddenly and quickly infiltrates the patient’s soft tissues (skin, muscles, tendons, blood vessels, etc.) In addition to the previously mentioned symptoms, other conditions such as fever, diarrhea and nausea may lead doctors to mistakenly diagnose this disease as the flu.

Ghastly enough are the visual conditions of this disease, but even more horrifying are the severe consequences of delayed treatment. Because NF spreads rapidly, a delayed diagnosis or treatment causes the infected area to deepen, increasing the difficulty of the already troublesome treatment regimen. Even with prompt treatment, the fatality rate still hangs high at around 25 to 35 percent, some 50 times higher than COVID-19 and even comparable to the overall death rate of cancer 5 years after diagnosis at 28.9 percent.

So, what’s the deal? Why is this bacterial infection so fatal?

“The first and most important step for [treating] infectious diseases [that] progress with terrifying speed is to characterize the specific organism that causes the infection,”

Dr. Huanzi Zhong, Ph.D.

To start with, let’s take a look at the disease’s origin. It is important to clarify that NF is actually a very general term. It is not associated with a certain type of bacteria, but instead summarizes the common symptoms caused by different types of bacteria. In fact, according to Dr. Huanzi Zhong, Ph.D., from the University of Copenhagen, a vast variety of pathogenic bacteria can cause the flesh-eating disease, including but not limited to group A Streptococcus, Vibrio vulnificus, Escherichia coli (E.coli), and Klebsiella pneumoniae.

Bacteria can be gram-positive or gram-negative. The bacteria are separated into the category of positive or negative according to the result of Gram’s method of testing which focuses on the thickness of the peptidoglycan in the bacterial cell wall and aerobic or anaerobic. Additionally, the disease often originates from a combination of bacterial strains (or species), referred to as a polymicrobial infection.

The most common cause of necrotizing fasciitis is a polymicrobial infection made up of a mixture of the Streptococcus and Enterobacteriaceae strains. Like these two groups, many other bacteria responsible for NF are also equally commonplace. Yet Dr. Zhong points out most bacteria from these genera (or family) are normally harmless. Some non-toxic bacteria are even beneficial to the specific organ they survive in. And with other possibly toxic strains, our immune system can counter them before they overrun our bodies. Therefore, necrotizing fasciitis is not often caused by minor trauma, but rather by immune defects, medical comorbidities or prior infections. In other words, as prevalent as these bacteria are, they rarely cause a normal, healthy human to display significant symptoms in a week or less.

Reports show that Vibrio vulnificus is another common source of flesh-eating disease. Because this bacterium mostly resides in seawater, patients have discovered symptoms after injuring themselves while visiting the beach or after eating raw seafood. Unlike the previous polymicrobial infection, the V. vulnificus infection attacks both healthy and unhealthy bodies indiscriminately. That said, the pathology for monomicrobial and polymicrobial NF infections are considerably similar. First, the bacteria proliferate inside the human body. They then release various toxins, such as the metalloprotease VvpE from V. vulnificus and streptolysins S and O from group A Streptococcus. These toxins aggressively attack the soft tissues of the human body, killing skin and muscle cells. In some circumstances, toxins can even cause shock syndrome, where blood flow is blocked and organ dysfunction occurs leading to a deadly situation.

What do medical professionals do if these symptoms arise in their patients?

“The first and most important step for [treating] infectious diseases [that] progress with terrifying speed is to characterize the specific organism that causes the infection,” Dr. Zhong says. She points out that rapid diagnostic technologies show promising potential in “characterizing infectious pathogens from humans (e.g., blood, saliva, urine, or stool) and environmental samples (e.g., food, soil, water or medical devices)” in less than 2 hours. For example, the syndromic testing company BioFire Diagnostics has begun manufacturing a PCR-based diagnostic chip that can identify all existing infectious diseases in a sample, all while processing as many as 175 samples per day. Metagenomic DNA sequencing is a powerful method for detecting possible pathogens that are not included in the above-mentioned diagnostic products.

So if we can efficiently diagnose NF, can we treat it just as easily?

Unfortunately, Dr. Zhong is not as optimistic about necrotizing fasciitis treatments. Depending on the type of pathogen, clinicians today usually prescribe different kinds of antibiotics to combat NF. Fighting the gram-positive group A Streptococcus strain for example, requires antibiotics that are very different from those used to treat gram-negative (more resistant) bacterial infections (e.g., Streptococcus and E. coli). However, due to antibiotics overuse, many pathogens have developed multi-drug resistance, which Dr. Zhong recognizes as one of the key reasons why the flesh-eating disease is so fatal. To tackle this issue, researchers have pinned their hopes on bacteriophage therapy. Bacteriophages, a type of virus, can be used to attack specific pathogenic bacteria while keeping other cells in our body safe. However, this treatment for NF remains unauthorized by the Food and Drug Administration as the technology is still in the early stages of development.

So, if there are limited options for treating an infection, how worried should we be?

First, we need to remind ourselves the likelihood of contracting NF is very low. Around the world, there are only about 0.6 cases per 100,000 people annually and many patients have a pre-existing immune deficiency. A simple comparison demonstrates how low this rate is. Car accidents kill 11.2 people out of 100,000 persons annually in America alone and cars are still driven regularly without any major concern.

There’s no need to live your life in fear of NF, more so because precautions can be taken against it. According to the CDC, good wound care is necessary to prevent skin infections. This includes washing wounds with soap or disinfectants, consulting doctors promptly if the trauma is deep or severe and avoiding wound contact with potential pathogen-containing sites like natural bodies of water, public swimming pools, etc.

There is also no need to worry about interpersonal infection, as little evidence shows the disease to be contagious. To prevent the V. vulnificus infection specifically, Dr. Zhong suggests not eating raw seafood or simply making sure to choose restaurants that have negative results for pathogen and parasite testing. Overall, it is important to simply raise awareness about this disease and thereby lower the risk of getting infected. Just like wearing a mask when we go outdoors or buckling up when in a car, risks cannot be eliminated entirely, but taking precautions throughout our daily lives can keep them at their lowest.

- Necrotizing fasciitis (NF) is a form of bacterial infection, also known as flesh-eating disease. The disease quickly infiltrates the patient’s soft tissues.

- Even with prompt treatment, the fatality rate remains high at around 25 to 35 percent.

- There are limited options for treating an infection. However, the likelihood of contracting NF is very low. Around the world, there are only about 0.6 cases per 100,000 people annually.

Sources

- https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00256-013-1813-2

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2762295/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4199388/

- https://sfamjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1462-2920.13955

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC90351/

- https://www.iihs.org/topics/fatality-statistics/detail/state-by-state#yearly-snapshot

Editorial Team

- Chief Editor: Shivani Patel

- Team Editor: Sydney Yan

- Creative Team Manager: Maya Hofstetter

- Social Media Team Manager: Karishma Goswami

- Image Credits: Adwaith Hariharan

Mentor

- Carol Haggans, MS, RD, is a Scientific and Health Communications Consultant in the Office of Dietary Supplements, National Institutes of Health

Content Expert

Huanzi Zhong, Ph.D. studied genetics, in particular, microbial pathology, at the University of Copenhagen.