In Brief

- Some scientists are investigating the emergence of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

- Mutations are a natural result of viral replication. One way to think of a virus mutating is a long game of telephone.

- Discovering the origins of the novel coronavirus could actually help us prevent a future virus from spiraling into a pandemic.

Let’s be honest, who doesn’t want to move on from the COVID-19 pandemic? 2020 has felt like a nightmare: the staggering death rate, loneliness and economic turmoil. The thought of returning to the normal routines of work, school, travel and friends may be tantalizing, but the novel coronavirus isn’t going to disappear overnight. The whole world wants to leave the painful events of the year behind, but we can’t just forget the past.

SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, is a recent addition to human pathogens, with most researchers agreeing it emerged towards the end of 2019 in Wuhan, China and spread across the world from there. Scientists know little about it compared to other viruses such as polio or the common flu, which makes COVID-19 difficult to treat and prevent worldwide. Additionally, though some countries have had experiences dealing with related epidemics (like MERS or SARS), the majority of the world was blindsided by the emergence of SARS-CoV-2. To move forward from the COVID-19 pandemic, scientists need to unravel its past: how it emerged, how it first spread and how it has changed.

While the phrase “COVID-19 research” may call to mind thoughts of vaccine development and mask testing, there are scientists researching every facet of this novel virus, down to its emergence. To piece together how SARS-CoV-2 first evolved, researchers across the world are using many methods, such as analyzing the genetic history of the virus in both humans and animals.

Lucy van Dorp is a senior research fellow in the University College London Genetics Institute, studying the evolution of SARS-CoV-2’s using genomics. Though van Dorp’s past research has mainly focused around studying the genetics of bacteria, she and her colleagues shifted to SARS-CoV-2 in March 2020. The group began studying the virus’s genomic data after the first genome was shared online on January 5, 2020 (Wu et al.), allowing scientists across the world to compare the initial viral sequence to later sequences. Van Dorp and her collaborators are using comparisons to the first sequence to study how the virus has evolved. They have identified at least 198 filtered recurrent mutations from the original DNA in the SARS-CoV-2 genome.

Mutations are a natural result of viral replication. A common misconception, van Dorp emphasizes, is that “people hear mutations and they associate that as a bad thing. . . but most mutations have no impact on the virus. From my perspective, mutations are very useful because we can use them to track the evolution of the virus and follow how it is transmitting around the world.”

One way to think of a virus mutating is a long game of telephone. As a message is passed around a group of people, the words change slightly. If each person in the group recorded what they heard from the previous player, an accurate timeline could be put together to pinpoint major message changes. The same is true for genetic sequences. Researchers could see when and where the virus’s genes changed over time if they compared data from when a virus was first discovered to a future version which has acquired mutations. In a global pandemic, this is especially valuable because it allows scientists to gather accurate data about how fast a virus is spreading and evolving. van Dorp says SARS-CoV-2’s mutations could “become a useful toolkit to reconstruct transmission between patients – some kind of tracking and tracing – with genomic data already informing us on where we have community transmissions versus imported cases.” In other words, the virus’s mutations could be used as a form of contact tracing in order to link an outbreak of infections back to their source.

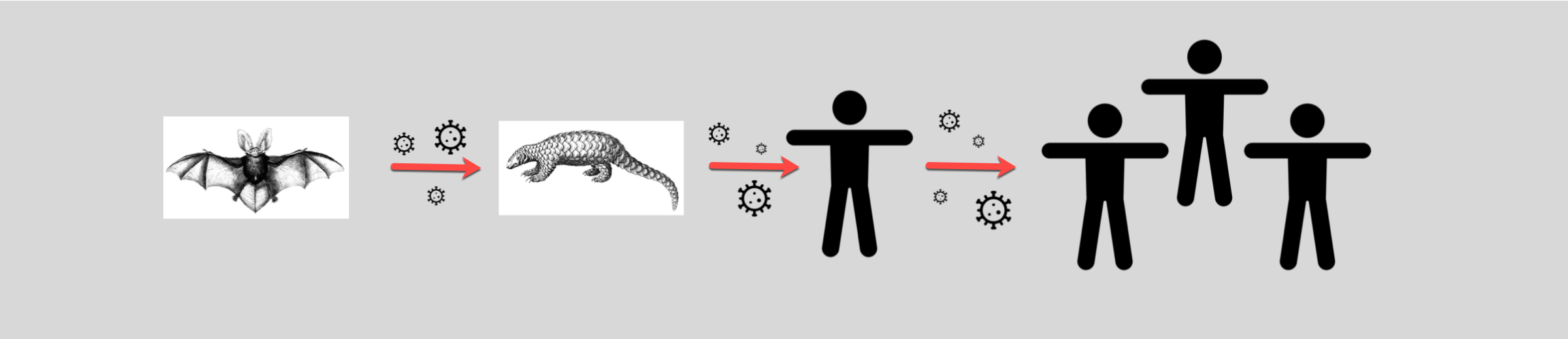

Van Dorp and her fellow researchers studied the differences between 7,666 SARS-CoV-2 genomes from humans around the world. They found the genomes shared a common ancestor towards the latter part of 2019. This suggests late 2019 as the time period when the virus first progressed from animals to humans. SARS-CoV-2 is a zoonotic virus, meaning that its ancestor existed in some form in animals before “spilling over” to humans. Van Dorp clarifies: “in all likelihood, we had a jump from an animal reservoir into the human population ….but nailing down what that animal reservoir may have been is a little bit more tricky”.

Many believe SARS-CoV-2 originated in a wet market in Wuhan brimming with hundreds of animals being sold for food or medicine in open-air stalls. Geneticists taking samples from the Wuhan market’s animals discovered the strain of SARS-CoV-2 that infects humans was 96% similar to one found in horseshoe bats (named BatCoV RaTG13) in Yunnan province. Despite this similarity, scientists have noted the bat and human viruses aren’t actually that close. Van Dorp explains “they happen to be the closest thing that we’ve sequenced, but these genomes are actually decades divergent from SARS-CoV-2.” She adds “though they may point to a plausible common ancestor in bat reservoirs.” This means even though the virus may have originally emerged in bats, it could also have spread through one or more intermediary hosts before transmitting into humans. If the SARS-CoV-2 virus was a game of telephone, the first player in the game who comes up with the phrase may have been the horseshoe bat, but there must have been at least one other participant that whispered a modified phrase to humans.

One of the proposed suspects is the Malayan pangolin, a scaly mammal that was being sold at the same Wuhan market. Because countless animals were kept in close quarters at that market, a potential virus could have easily spread between animals and the humans eating them or working with them. A May 2020 study showed parts of the virus strain found in pangolins (called pangolin-CoV-2020) are highly similar to that found in the human virus. This suggests pangolins could hold clues to the missing link. Though the study does not prove SARS-CoV-2 evolved directly from pangolins, the authors do say the animals could be natural hosts of a closely related virus. Whether pangolins, bats or a combination of other mammals helped incubate and spread the virus, it is clear to many researchers, including van Dorp, that SARS-CoV-2 “actually seems to be quite a generalist,” meaning the virus could likely exist and transmit in many different mammalian carnivores.

The average person may have little interest in which animal interaction brought COVID-19 to humans because it doesn’t hold the answer for how we can treat or vaccinate against the disease. But discovering the origins of the novel coronavirus could actually help us prevent a new virus from spiraling into a pandemic. Understanding precisely how COVID-19 transferred from animals to humans could allow scientists to know which species to test regularly and to keep out of crowded areas or from wildlife trade networks. Similar to the use of masks to prevent the spread of disease, keeping a close eye on these animals could disrupt the viral game of telephone which allowed COVID-19 to emerge.

Content Expert

Dr. Lucy van Dorp is a Senior Research Fellow based at University College London Genetics Institute. She researches genetic diversity and the genetic history of pathogens including COVID-19, tuberculosis and malaria.

SOURCES

- Lucy van Dorp, Mislav Acman, Damien Richard, Liam P. Shaw, Charlotte E. Ford, Louise Ormond, Christopher J. Owen, Juanita Pang, Cedric C.S. Tan, Florencia A.T. Boshier, Arturo Torres Ortiz, François Balloux, Emergence of genomic diversity and recurrent mutations in SARS-CoV-2, Infection, Genetics and Evolution, Volume 83, 2020, 104351, ISSN 1567-1348, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104351 .

- Muhammad Adnan Shereen, Suliman Khan, Abeer Kazmi, Nadia Bashir, Rabeea Siddique, COVID-19 infection: Origin, transmission, and characteristics of human coronaviruses, Journal of Advanced Research, Volume 24, 2020, Pages 91-98, ISSN 2090-1232, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2020.03.005 .

- Liu P, Jiang JZ, Wan XF, Hua Y, Li L, et al. (2020) Are pangolins the intermediate host of the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2)?. PLOS Pathogens 16(5): e1008421. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1008421 .

- Ye, Z. W., Yuan, S., Yuen, K. S., Fung, S. Y., Chan, C. P., & Jin, D. Y. (2020). Zoonotic origins of human coronaviruses. International journal of biological sciences, 16(10), 1686–1697. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.45472

Chief Editor: Shivani Patel

Team Editor: Lasya Balachandran

Creative Team Manager: Maya Hofstetter

Social Media Team Manager: Karishma Goswami

Cover image credits: Freepik.com, body by Adrien Coquet from the Noun Project, virus by Ayub Irawan from the Noun Project.

This article was written by Maya Hofstetter. Maya and the cSw student editing team would like to thank Sybil Barnes for serving as a mentor on this story. Sybil is the Assistant Director of Communications at the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. As always, before leaving a response to this article please view our Rules of Conduct. Thanks! -cSw Editorial Staff