Among the extensive assortment of household pets—from furry guinea pigs and vocal parakeets to scaly bearded dragons—dogs are the most popular pet around the world. Commonly known as ‘man’s best friend,’ dogs not only offer valuable companionship, but also have remarkable capabilities. Throughout history, humans have trained canines to detect mines in battlefields, guide owners with visual impairments, and even sniff out diseases like diabetes and cancer. Now, our four-legged friends are serving as key contributors in the search for cures to rare human muscular disorders.

Humans started domesticating dogs only 13,000-30,000 years ago by pairing pups with desired traits together. Unfortunately, this matchmaking process caused many breeds to simultaneously inherit diseases. Among the many diseases are congenital myopathies – genetically-inherited mutations affecting muscle cells – which interestingly enough, are also shared by their human counterparts.

Myotubular myopathy (MTM) is a specific congenital myopathy that affects 1 in 50,000 newborn boys. In both humans and dogs, the mutation typically only affects males. Why? The mutated gene is located on the X chromosome. In the genetic makeup of humans and other mammals, biological sex is controlled by a pair of sex chromosomes. In females (XX), one normal gene generally overrules the defect. Meanwhile, in males (XY), the defective gene causes a difference as clear as night and day. Boys are born with difficulty maintaining life-sustaining functions such as breathing, feeding, and motor control. Depending on the severity, boys may succumb to the mutation early in life.

Unearthing a Possible Treatment

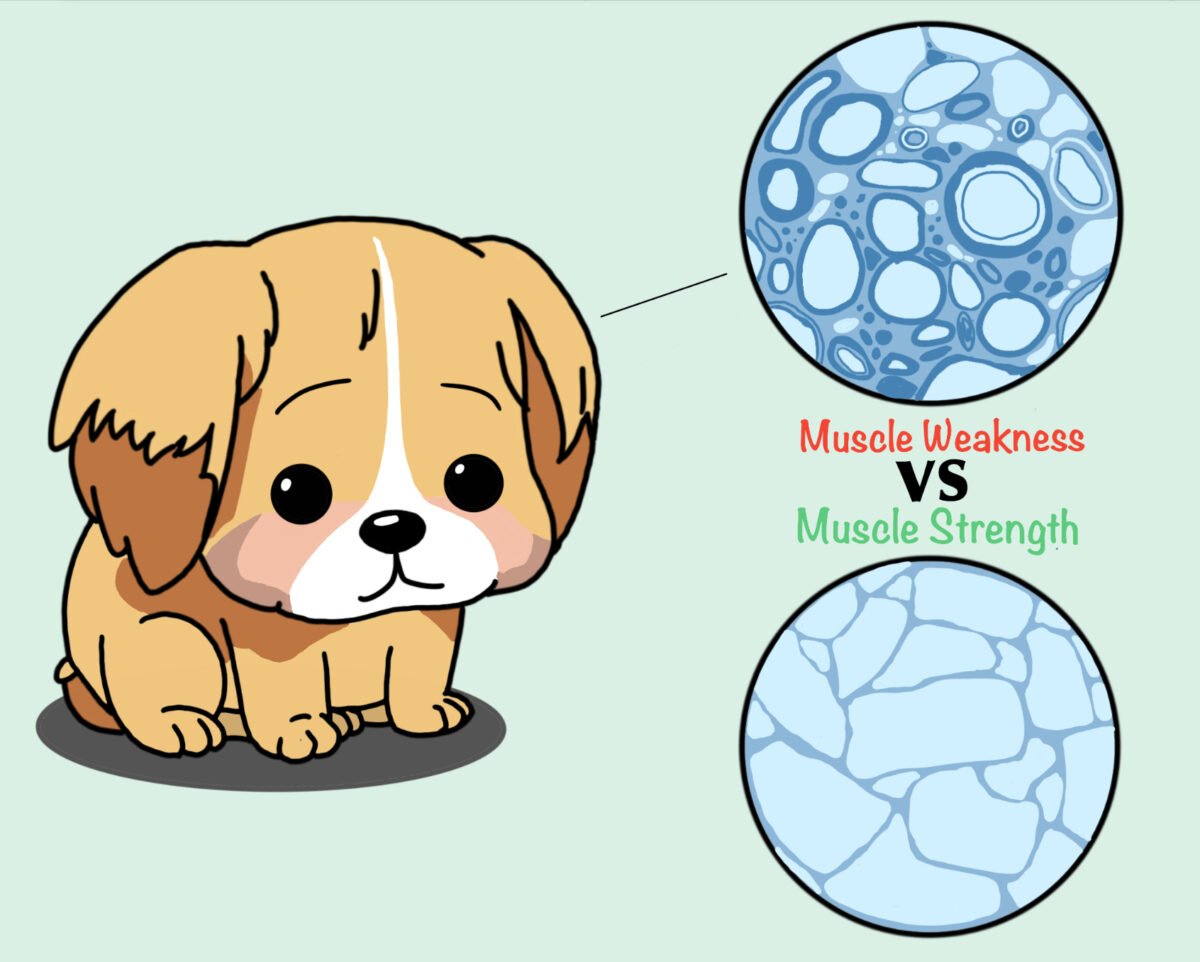

Researchers are attempting to use modern technology like gene therapy to treat myotubular myopathy. Normally, muscle fibers are long tubular structures that consist of many cells with nuclei lining its edges. The presence of MTM causes the nuclei to become embedded in the center of the fiber. Theoretically, using gene therapy techniques where a viral ‘vector’ delivers a healthy copy of the MTM gene could provide the body with the missing protein and repair the muscle fiber.

To test if this technique would work, scientists injected viruses carrying the MTM gene into mice and found that instead of dying at two to three months of age, the mice stayed healthy. Gene therapy successfully cured the mice! Following these experiments, it quickly became apparent that researchers needed to test this method on other animal models. It may be easy to treat a mouse, but to skeptics, it seemed unlikely the same approach would also help humans.

Moving Doggy Muscle

Dr. Alan Beggs, director of the Manton Center for Orphan Disease Research at the Boston Children’s Hospital has studied congenital myopathies since the 1990s, enrolling more than 1,000 patients in genetic studies. In 2008, Dr. Beggs joined forces with Alison Frase, the mother of one of his patients; and together, they stumbled across a unique litter of Labrador retrievers in Canada.

“They all had been born essentially looking normal,” Dr. Beggs explained. “But by the age of three or four months, they started to get weak and have a stooped appearance.”

Dr. Beggs and other researchers used gene sequencing, a relatively non-invasive process that revealed that the puppies possessed a canine variant of myotubular myopathy. By taking advantage of this opportunity, researchers could test potential treatments—such as gene therapy—to alleviate the disease. Success with the pups could indicate the treatment’s efficacy in larger mammals; crucial information in order for treatments to advance to clinical trials, that is, trials conducted on humans.

While animal research is conducted with the goal to benefit human medicine, contrary to common misconception, the research benefits our animal friends as well. Anatomical similarities, especially between mammals such as dogs and humans, mean that many of the same medicines used to treat boys with myotubular myopathy can be used to lengthen the lifespans of pets with MTM.

Testing the pups with gene therapy methods similar to those used with mice, Dr. Beggs and his colleagues noticed tremendous results.

“The first treated dogs are ten to eleven years old now and they’ve got great muscles,” Dr. Beggs remarked. They would have died well before their first birthday if they hadn’t been treated.”

Along with careful observation of treated pups, Dr. Beggs and his colleagues strictly adhere to animal welfare oversight when testing their MTM gene therapy treatments. In fact, every research project involving animals in the United States is overseen by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), which creates and enforces policies for research conducted on animals. The committee strives to replace the use of animals whenever possible, reduce the number of animals needed in studies, and refine experiments to minimize discomfort. Thanks to the IACUC’s regulation, all animals at research institutions—including the dogs that Dr. Beggs works with—receive meaningful and humane care.

Forging Forward Toward Muscle Gains

Further research has made significant headway toward a cure for myotubular myopathy. In terms of recent trials conducted on humans with MTM, genetic therapy has been remarkably effective.

“Boys who never would have walked are now walking,” Dr. Beggs added. “Boys that had a tracheostomy to help them breathe have had that breathing instrument removed and can now breathe on their own.”

Unfortunately, gene therapy treatment for MTM has not been without drawbacks either. Clinicians have discovered that the treatment can cause a fatal liver defect, a side effect specific to humans. The clinical studies have since been halted and Dr. Beggs speculates that “they are probably not going to be restarted with the same viral vector to deliver the gene.” While this is a setback, it is by no means the end of using gene therapy as a potential treatment for MTM.

“Myself and others have been working on newer viruses that we can give at a lower dose,” Dr. Beggs expressed. “We hope that the lower dose will be safer.”

Due to the relative newness and undergoing development of gene therapy, treatment is not yet widely accessible to boys with MTM or pet owners seeking to treat their affected dogs. However, gene therapy studies involving affected pups have made the use of modern technology to treat muscular disorders more prevalent. Now, current MTM studies are primarily conducted on zebrafish—a unique model for biomedical research due to its fully sequenced genome and easy genetic manipulation, among other characteristics.

“Despite what has happened,” Beggs noted, “the families don’t want us to give up this research.”

More than just a boy’s best friend, dogs are helping researchers discover a cure that has the potential to save many lives—human and pup alike.

- Myotubular myopathy (MTM) is a congenital disease that affects one in 50,000 newborn boys. It can also be found in dogs.

- The disease is caused by a mutated gene located on the X chromosome.

- Researchers are attempting to use modern technology like gene therapy to treat myotubular myopathy – first in animals such as mice and dogs – in the hopes of a new treatment for human and animal patients.

Sources

Fliesler, Nancy. “Restoring Muscle Function in a Rare, Devastating Disease: Part 1.” Boston Children’s Hospital, 16 May 2013, answers.childrenshospital.org/myotubular-myopathyrestoring-muscle-function-in-a-rare-devastating-disease-part-1/. Accessed 19 Aug. 2023.

“Restoring Muscle Function in a Rare, Devastating Disease: Part 2.” Boston Children’s Hospital, 16 May 2013, answers.childrenshospital.org/myotubular-myopathy-enzyme-replacement/. Accessed 19 Aug. 2023.

“Penn Developed Gene Therapy for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Safely Preserves Muscle Function.” Penn Medicine News, The Trustees of the U of Pennsylvania, 7 Oct. 2019, www.pennmedicine.org/news/news-releases/2019/october/penn-developed-gene-therapy-for-duchenne-muscular-dystrophy-safely-preserves-muscle-function. Accessed 19 Aug. 2023.

Rodriguez, Barbara. “Gene Therapy Treats Muscle-Wasting Disease in Dogs.” Institute for Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine at the University of Washington, iscrm.uw.edu/gene-therapy-treats-muscle-wasting-disease-in-dogs/. Accessed 19 Aug. 2023.

Switonski, Marek. “Impact of gene therapy for canine monogenic diseases on the progress of preclinical studies.” Journal of applied genetics vol. 61,2 (2020): 179-186. doi:10.1007/s13353-020-00554-8

Editorial Team

- Chief Editor: Annika Singh

- Team Editor: Aanya Bulusu

- Image Credit: Maggie Liu

- Social Media Lead: Melia Hillman

Mentor

Amy Puffenberger holds a Bachelor of Science in Film and Video Production (2005) from Grand Valley State University and a Master of Arts Management (2010) from Carnegie Mellon University. While completing her master’s degree, Amy worked with both Pittsburgh Filmmakers and the Arts Education Collaborative, and later served as the Manager of Educational Outreach at WQED Multimedia, the PBS-affiliate in Pittsburgh, PA, and the nation’s first community-supported public broadcaster.

Content Expert

Alan Beggs, Ph.D., is the Director of the Manton Center for Orphan Disease Research at Boston Children’s Hospital and a professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School. Dr. Beggs is internationally recognized as an expert in the genetics of congenital myopathies. He specifically focuses on the pathophysiology of rare genetic conditions in animal models and human patients to identify treatment methods.